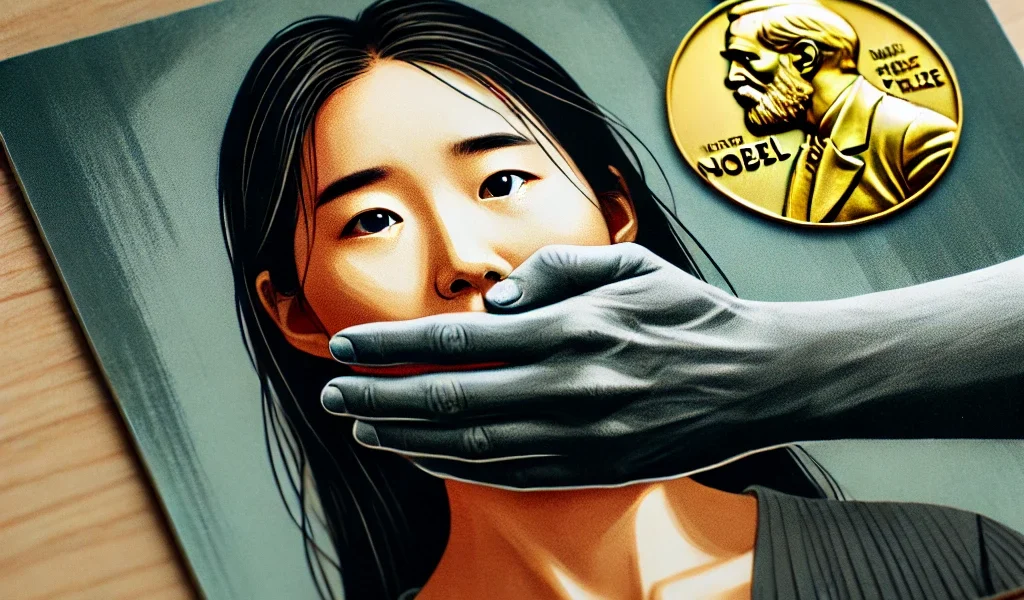

In an unprecedented achievement, Han Kang became the first Korean and the first Asian female writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Recognized by the Swedish Academy for her “poetic prose that confronts historical trauma,” Han’s work has gained international acclaim. However, beneath the global recognition lies a troubling chapter in her career: Han Kang was once blacklisted by the South Korean government during the Park Geun-hye administration.

The Blacklist and Its Origins

The existence of a cultural blacklist in South Korea came to light in the mid-2010s, revealing the names of thousands of artists, writers, filmmakers, and performers who were systematically excluded from government support and funding. The blacklist was a deliberate attempt by the Park Geun-hye administration to suppress dissenting voices in the cultural and artistic community.

Among the blacklisted was Han Kang, a celebrated novelist whose work has resonated with readers across the globe. Ironically, while her international profile was rising, back home, she was marginalized by her own government. The government perceived her and others as potential threats due to their critical views or involvement in politically sensitive issues.

“The Boy Is Coming” and Censorship

One of Han Kang’s most notable works, The Boy Is Coming (소년이 온다), is a harrowing novel based on the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, a democratic movement violently suppressed by the South Korean military. The novel explores the trauma and loss experienced by a young boy caught in the crossfire of the uprising, offering a powerful critique of authoritarian regimes.

In 2014, The Boy Is Coming was excluded from the Sejong Books selection process, a government-backed literary promotion program. Testimonies later revealed that officials scrutinized the book for “problematic” content, effectively conducting pre-publication censorship. Han’s critical portrayal of a dark chapter in South Korea’s history made her a target of the government’s attempts to silence voices of dissent.

The Man Booker Prize and International Recognition

In 2016, Han Kang achieved global recognition when her novel The Vegetarian won the prestigious Man Booker International Prize. The novel, a story about a woman who decides to stop eating meat in defiance of societal expectations and patriarchal control, captivated readers worldwide. It was praised for its exploration of identity, body autonomy, and resistance.

When Han Kang won the Man Booker Prize, Park Geun-hye, then president of South Korea, notably did not send a congratulatory message, a customary gesture for such a significant national achievement. This silence was seen by many as a continuation of the government’s disregard for artists and writers who challenged the status quo.

Blacklist Exposure and Cultural Repression

The exposure of the blacklist in 2017 sent shockwaves through the South Korean cultural community. The list was extensive, affecting more than 9,000 individuals and 400 organizations, including internationally recognized artists like Han Kang, film directors like Park Chan-wook, and other significant figures in the arts.

According to Lee Won-jae, the spokesperson for the investigation into the blacklist, this was not an isolated action by one government body. It involved numerous organizations, from the Blue House (South Korea’s executive office) and the National Intelligence Service to the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, as well as South Korea’s embassies abroad.

In particular, Lee mentioned that prominent writers such as Kim Yeon-su, Kim Ae-ran, and Lim Chul-woo, alongside Han Kang, were systematically excluded from major international events such as the Paris Book Fair. The government even influenced cultural promotions abroad, a deeply symbolic move illustrating the lengths to which it would go to stifle critical voices.

While the blacklist represented a direct attack on artistic freedom, its broader implications for society and democracy were chilling. The control exerted over cultural production mirrored the authoritarian practices that South Koreans had fought against during the country’s democratic movements. Han Kang’s works, which often explore themes of oppression and resistance, stand as a testament to the importance of freedom of expression in confronting these dark forces.

What the Blacklist Taught Us

The case of Han Kang and her fellow blacklisted artists highlights the intersection of art, politics, and power. Even in a democracy, the suppression of artistic expression can occur when political authorities feel threatened by critical perspectives. However, as Han Kang’s continued success demonstrates, creative resilience can withstand even the most intense efforts to silence it.

In the years since the exposure of the blacklist, there have been efforts to reform the cultural policies of South Korea, ensuring that no such systematic repression occurs again. Han Kang remains a powerful figure in both the literary and political spheres, her works continuing to resonate with readers who see in her stories a reflection of their own struggles for identity, freedom, and justice.

Conclusion: A Symbol of Resistance

Han Kang’s journey from blacklisted author to Nobel Prize-winning novelist is not just a personal victory but a symbol of the broader struggle for artistic freedom in South Korea. Her works, from The Boy Is Coming to The Vegetarian, challenge readers to confront uncomfortable truths about society, history, and power. As the world continues to celebrate her literary achievements, Han Kang stands as a reminder of the enduring strength of the written word in the face of oppression.